A newspaper article about Thistleton &

Elswick, 1912.

Elswick, one of the best known of the villages 'twist Ribble and Wyre, is of

remarkable interest this year to Fylde visitors and residents, for there has just been celebrated

in this beautiful spot the 250th anniversary of the ejection of ministers in 1662. There was no

actual ejection from Elswick, but the district gave birth to and succoured a minister who suffered

the penalty of conscience.

To reach this interesting village from this corner of the Fylde several routes are possible—through

Kirkham, through Blackpool and Singleton, and through Weeton and Thistleton.  The latter is the most direct way, and

offers more pleasant and less-frequented roads. It is curious to note how Weeton is the centre

of the Fylde ; all roads lead to the village, and the prettiest paths to the beauty spots of

the district come within its boundaries. Passing close by the Weeton windmill, built exactly a

century ago, the road to Thistleton winds through some delightfully wooded country, the

scenery in the distance dwindling away to the fells, which rear their heads against the sky

line. The latter is the most direct way, and

offers more pleasant and less-frequented roads. It is curious to note how Weeton is the centre

of the Fylde ; all roads lead to the village, and the prettiest paths to the beauty spots of

the district come within its boundaries. Passing close by the Weeton windmill, built exactly a

century ago, the road to Thistleton winds through some delightfully wooded country, the

scenery in the distance dwindling away to the fells, which rear their heads against the sky

line.

And the Fells stretch out in misty lines that

fade in the grey-blue distance,

Losing themselves in the fleecy clouds that wrap the shadowy heights,

Heights that are scarred by countless storms

and centuries' grim resistance

To the onset fierce of the northern winds,

and worn by a thousand fights.

Thistleton, the most picturesque hamlet of the Fylde, has been abundantly

favoured by Nature, and where Nature left off man began. The magnificent avenue of trees which line

the cobblestone paving have been pruned into shapely specimens, and the shadows of the dancing

leaves are cast upon old-world gardens. Here, at any rate, the suburban builder has not yet arrived

with his monotonous rows of red brick walls, and sweet-scented hawthorn hedges are sufficient

division walls.

All the way from the seashore the vegetation has been getting more abundant as the salt atmosphere

dies away, until, instead of the narrow-leafed willow we find handsome beech, ash and elm, and

occasionally a gnarled oak. Thistleton is a peaceful hamlet; indeed, so peaceful that in the

noontide hour, with the sun riding high overhead, the only sounds to be heard are the drowsy

humming of bees, the shrill piping of birds, the swish of the scythe of an ancient labourer as he

cuts the tall grass on the roadside, and the clatter of the farm wife's clogs on the cobblestones

of an adjacent yard. It is Nature's siesta.

The hamlet, too, shows how wonderfully Nature tones colours into perfect

sympathy, for here the complementary colours of green, red and white, have been so softened by the

Great Artist that they make a perfect picture. Nature never offends by crude effects. The people

are unspoiled by the hustle of modern town-life, and one finds in them the good nature that is

perhaps the outstanding characteristic of all rustic peoples. The farms, too, look prosperous, all

the outbuildings are modern and up-to-date, betokening a wise care, and everything is in contrast

to the time, half a century ago, when turnips were only to be seen growing in gardens.

Thanks to a most efficient supply of sign posts the way to Elswick is easy to find, and a run of a

mile brings us into the village where Fylde Nonconformity was cradled. The village is well worth

visiting for its quaint charms, apart from its historical association. The irregularity of the

cottages, jumbled in clusters of white-washed thatched dwellings, side by side with more imposing

brick residences, and the long, old-fashioned, free-flowering gardens produces an effect that is

delightful.

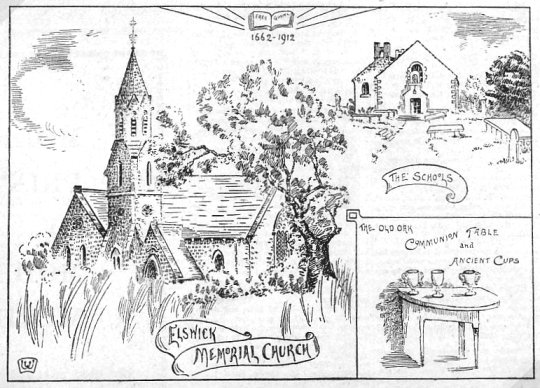

The "Elswick Memorial Church" stands at one end of

the village, and is quite a modern building, being erected in 1873: Adjoining is a structure

of grey masonry, now used as a school, which dates from 1753, but the records of the church go

back to 1649. The "Elswick Memorial Church" stands at one end of

the village, and is quite a modern building, being erected in 1873: Adjoining is a structure

of grey masonry, now used as a school, which dates from 1753, but the records of the church go

back to 1649.

In 1650 the Parliamentary Commissioners of the Commonwealth reported that "the

inhabitants, being fifty families and five miles from their parish church, had lately, with the

voluntary and free assistance of some neighbouring towns, erected a chapel," and the fifty families

desired it to be made a parish, and that a competent maintenance should be allowed to the minister.

In 1672 the chapel was seized by the Presbyterians when Charles II. had granted his indulgence to

Nonconformists.

History is blank as to the church for the first ten or fifteen years after 1650, but in 1672 the

Rev. Cuthbert Harrison, the first-known minister, obtained a license for the meeting-house at

Elswick Lees, for the use of such as did not conform to the Church of England and were of the

persuasion commonly called "Congregational." The use of the word "Congregational," in the licence,

is certainly noteworthy.

Cuthbert Harrison was, so far as can be ascertained, the only Fylde minister

ejected in 1662. A native of Newton, near Kirkham, he graduated B.A. at Cambridge. He was ordained

at Kirkham Parish Church according to the Presbyterian form, and we find that in 1651 he was

instituted Vicar at Singleton. Then he removed to Shankill, Armagh, in Ireland, where he suffered

ejection in 1662, and "narrowly escaped with, his life in a ragged disguise from England," whilst

his "beloved people preserved his goods for him."

With the royal licence mentioned, he settled at Elswick, but the place was

closed shortly afterwards by Act of Parliament, and the licence declared illegal. Again he

experienced persecution and held services, "very privately in the night," in his own house at

Bankfield, or in the houses of his congregation.

His son says he practised physic with good success, whereby he supported his

family and gained the favour of the neighbouring gentry. He also baptised children and married

people, and for this, and preaching, he was persecuted by Vicar Clegg, of Kirkham. Excommunication

did not deter him from attending the church at Kirkham, and Dr. Porter records some stirring

incidents.

Mr. Clegg, a one occasion, was so much disturbed on seeing the irrepressible

communicant in the chancel, whilst he was engaged with the sermon, that he lost the thread of his

discourse, and being unable to find the place amongst his notes, was silent for some time. Smarting

under the additional annoyance the Vicar ordered the churchwardens to eject Mr. Harrison from the

building at once, but that gentleman refused to leave unless Mr. Clegg, in person, performed the

duty of turning him out. Incensed at his show of obstinacy, the Vicar appealed to Christopher

Parker, of Bradkirk Hall, a justice of the peace, who was seated within six feet of Mr. Harrison,

to remove him, but the magistrate refused to act in the matter, and Mr. Clegg was obliged to

descend from the pulpit and undertake the unpleasant task himself. He walked up to the offender,

and, taking him by the sleeve, desired him to go out from the church.

Mr. Harrison went peaceably with the Vicar, but had no sooner passed out through

the chancel door than he exclaimed in, a loud voice, "It is time to go when the devil drives."

Shortly after this episode Mr. Clegg sued Cuthbert Harrison for the sum of 120s., being a fine of

20s. per month, extending over six months, for non-attendance at the Parish Church.

The defendant pleaded that when he had attempted to attend the service at

Kirkham, he had been ejected from the church by the plaintiff himself, and the judge who summed up

the evidence, in favour of the defendant, remarked, "There is fiddle to be hanged and fiddle not to

be hanged." The verdict went against Mr. Clegg.

Cuthbert Harrison died in 1681, still under the ban of excommunication and "a

great entreaty," writes his son, "was made to Mr. Clegg to suffer his body to be buried in the

church. He was prevailed upon,. and Mr. Harrison was interred a little within the great door, which

has since been the burial place of the family." The following epitaph is said, by his son, to have

been fixed upon 'Cuthbert Harrison's grave, by Mr. Clegg:

"Here lies Cud, Who never did good,

But always was in strife;

Oh ! let the Knave Lie in his gave,

And ne'er return to life."

This epitaph was altered by a local rhymster to:—

"Here lies Cud,

Who still did good,

And never was in strife,

But with Dick Clegg,

Who furiously opposed

His holy life."

* * *

From the death of Cuthbert Harrison the record of ministers is complete, though

no minister was appointed until after the peaceful revolution of 1688. The registers of the Chapel

are in the custody of the Registrar General at Somerset House. Some of them are in a dilapidated

condition owing to an unfortunate accident, by which the registers slid off a table on to a fire in

1836.

The second minister was the Rev. Robert Moss, whose tombstone, adjoining the

path to the old school-chapel, records, "Here are interred the remains of the Reverend Robert Moss,

a worthy minister of Christ, a man generally esteemed and loved, who served his Lord in a useful

and exemplary manner a Elswick, 44 years, and died April 2nd, age, 71, A.D. 1759."

During Mr. Moss's ministry the second chapel was erected in 1753, and it is now

used as the school, after being renovated and extended in 1906. With the cessation of persecution

the Elswick Church flourished and became the centre of evangelisation for the countryside.

Many old families have family graves in the quiet churchyard, which is one of

those spots that one feels instinctively ought to be called by the old Saxon name, "God's acre."

Many tombstones are now indecipherable and others have quaint epitaphs, and th following lines, on

one of the ministers of the church, have a flavour of Goldsmith' country parson:

Inspired with zeal for his Redeemer's calls He preached His gospel and enforced

Hi laws, Wise to win souls, he laboured with success In turning men to God and righteousness.

|